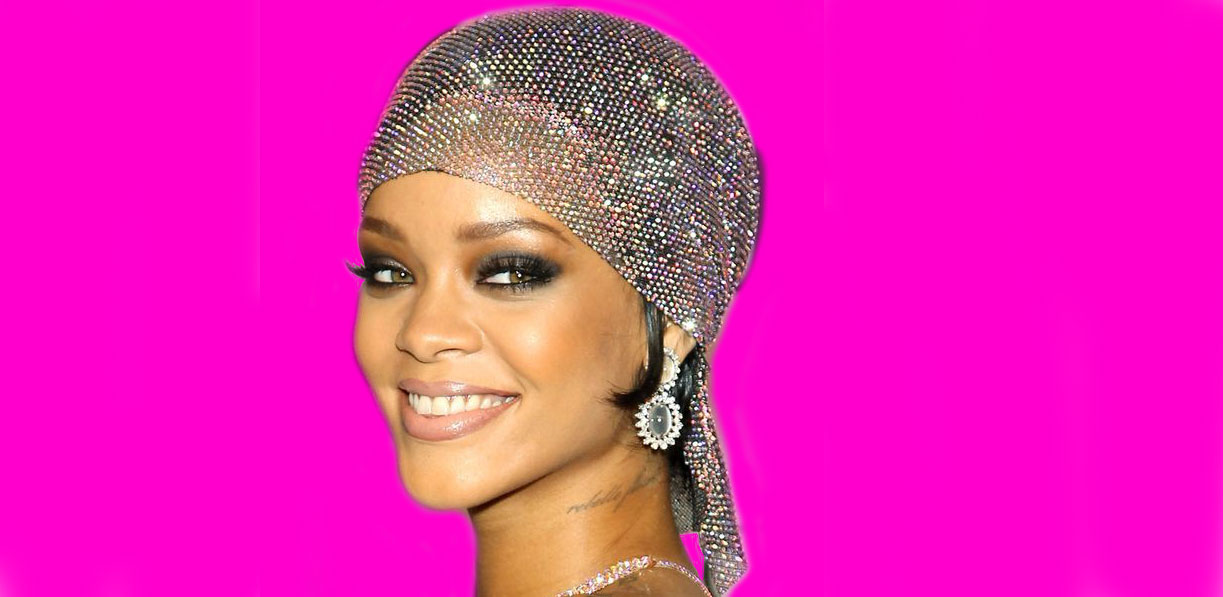

Last week, Rihanna appeared on the cover of British Vogue for the second time. The singer has been on a number of Vogue covers over the years, but this shoot in particular was a stand out, as the singer was wearing a Stephen Jones Millinery durag. This marked the first time anyone had worn a durag on the cover of Vogue, making the moment instantly historic.

In the past two decades, durags have gone from being a hidden article that’s snatched off before you leave the house, to an emblem of Blackness that’s worn in high fashion spaces.

The durag, a well-designed scarf meant to press down one’s curls for the effect of waves, has roots in the Antebellum South. Slaves were forced to wear headwraps to indicate inferiority, and mixed race slaves and free people, were required to wear them so that others would know that they weren’t white. Though it’s tough to pinpoint exactly when the durag was invented, it’s an extension of these scarves and other wraps used to set the hair.

In 2018, the New York Times wrote that the durag, which was then called a “tie-down,” could possibly be attributed to William J. Dowdy, who in 1979 invented the piece of fabric that would help maintain Black hair’s pattern after having been brushed extensively.

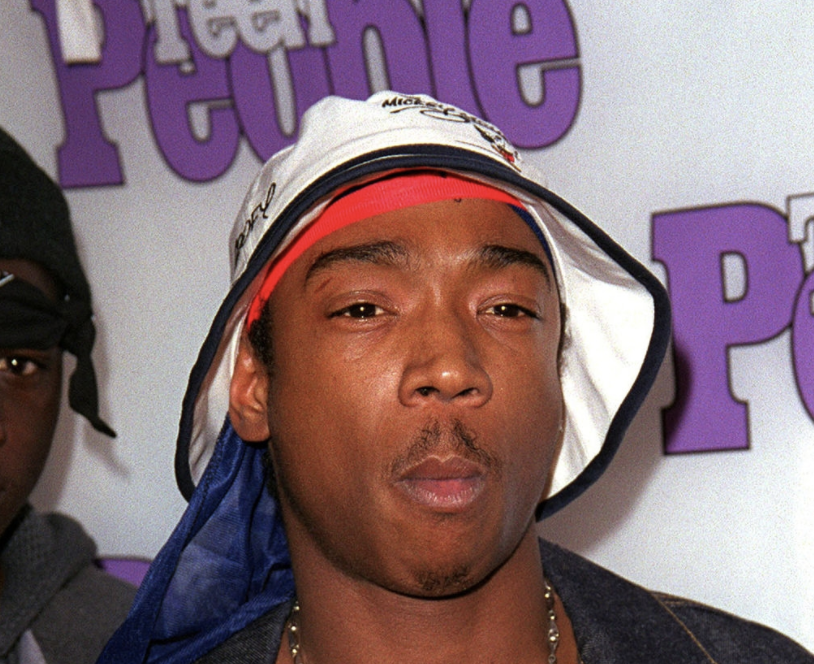

But until the late 90s and early 2000s, durags were still largely worn within the home and when someone was in transit. Before then, they were viewed as what helped bring an outfit together, as opposed to a part of the look itself. But as ghetto fabulous fashion — the celebration of (or aspiration to) upper class success, while maintaining a connection with more underground Black style trends, was incorporated into pop culture, Black entertainers became more comfortable wearing durags in music videos and for appearances. Rappers Ja Rule, Cam’ron, Eve, and Nelly were early aficionados for the mainstream appreciation of durags.

Ja Rule wore a a multicolored durag underneath his bucket hat at the Teen People Magazine’s What’s New In Teen Talent event in 2000.

Nelly wore a durag with a leather Louis Vuitton two-piece suit, courtesy of Dapper Dan, at the 2001 Grammys. His attendance at the prestigious award show, coupled with his luxury brand-adjacent threads, was a huge moment in the durag’s incorporation into high fashion. From then on, it was not uncommon to see celebrities at major events with their durag capes flying in the wind.

But this triumph was not without setbacks.

According to GQ‘s 2018 piece on durags, NFL owners banned durags in 2001, and in 2005, the NBA did the same. Durags were subsequently stigmatized and associated with criminality, which effectively pushed them out of the places that they had just recently been able to enter. It appeared to be a racist attempt to control Black expression, because although they were functional, durags were worn purely for fashion purposes as well, but one that that ultimately proved to be futile.

Since its inception, the culture of hip-hop has been overtaking conversations regarding popular fashion. Critics couldn’t help but notice how the early styles associated with the sound, such as shell-toe Adidas, were becoming sought after, and how people of all backgrounds were looking to hip-hop artists for the next big thing in fashion. Rappers’ taste-making abilities continued well into the new millennium, and as rap became a dominant artform, it was realized that white authorities could not keep a cap on Black style. This, along with defiant artists who never cared about respectability in the first place, is how durags were able to able to reemerge full force.

Rihanna played a pivotal role in the reintroduction of the durag and helped push the article to become as accepted, and widely discussed, as it is today.

The “Work” singer and businesswoman wore an iteration of the durag when she won the Style Icon award at the 2014 CFDA awards. Then, for her 2016 Video Vanguard performance at the MTV Video Music Awards, she hit the stage in a trailing mesh durag, and was decked out in a diamond ankh necklace, a fur-lined bra, crystal heels, and black trousers. Attending these shows, and winning coveted awards while wearing a durag sent a message that the headpiece was not just for a specific type of Black person or event. Durags had the potential to operate beyond racist and classist gazes and be looked at as useful, fashionable garments.

Rihanna also wore a durag in her most recent ad for Fenty, her high end clothing brand that lives under the LVMH umbrella. This is likely the most technically impactful instance of her wearing a durag, as she is the first Black woman to own a brand under the historical conglomerate. She is able to use her own global platform to bring the durag to the forefront of grandeur.

Ahead of the 2018 Met Gala, Solange Knowles posted a series of looks and asked fans to weigh in on which one she should wear to the annual ball. Her following gravitated towards a black, latex Iris van Herpen dress that was accented by a durag. The next night, Knowles appeared at the event in a lengthy durag with the phrase “MY GOD WEARS A DURAG,” written with crystals on the back. The night’s theme was “Heavenly Bodies: Fashion and the Catholic Imagination,” and Knowles used it as an opportunity to have her braided crown serve as a halo and her durag be an signifier of Black holiness.

Then, last summer, Beyoncé wore a Gucci durag for the Glasglow, Scotland stop of her joint tour with Jay-Z, On The Run II. As the first lady of music, and someone with the power to create a craze at the drop of the dime, her durag quickly made headlines and added to the conversation regarding durags’ place in luxury brand apparel.

This time period’s celebration of the durag is less of a reclamation, and more about Black people’s ability to take a piece of cloth meant to humiliate them, give it purpose, and make it fashionable. But that’s not new to us. We are accustomed to spinning hay into gold and flexing our ingenuity in the face of those who sought to make us feel less than.

The durag’s history, like our own, is rather complex. It has followed us for centuries, as we’ve blazed our own trail to glory, and has carefully walked in our footsteps to become a crown. It’s only fitting that we honor its status by wearing it in the most exclusive spaces.

Maybe all heroes do wear capes after all.