Women with lime green pigmentation, pointed hats and elongated, pimpled noses are one of the primary emblems of Halloween. They’re the ones plastered on the walls of elementary schools during the fall and who people aspire to look like when piecing together their costumes. When considering them through a more historical lens, we are commonly introduced to witches through the Salem witch trials — the infamous prosecutions of over 100 people following the exhibition of strange and unusual behavior in a Puritan town. In our learnings about one of the country’s first literal witch hunt, one person stands out; Tituba, an enslaved woman who was one of the first women to be accused of witchcraft.

We know Tituba was of color, with varying accounts describing her as Native Southern American or half African, half Native. She is often called “the Black Witch of Salem,” but historian Elaine G. Breslaw traced her roots to modern Venezuela, believing the girl was sent to Barbados as a slave. She was an enigma in origin and in life overall, as not much is known about her following the Witch Trials. Also, during that time, it was not unusual for differing non-white races (within America) to be conflated.

As a teenager, Tituba was bought by Samuel Parris in Barbados and relocated to Massachusetts in 1680. It was within Reverend Parris’ home that the questionable activity she is inextricably linked to began to take place. In 1692, a group of young girls, including Parris’ own daughter, Betty, and his niece, Abigail, began to bark like dogs and contort their bodies after allegedly attempting to divine their future. As their caregiver, Tituba was blamed.

Whispers of witchcraft have been unsurprisingly common since biblical times, with at least two “witches” being mentioned in the Old Testament. Sometimes billed as “heresy” (which was what Joan of Arc was accused of when she was sentenced to death in 1431), any woman expressing a basic freedom in parallel of religious doctrine was subject to whatever cruelty misogyny could invent. Patriarchy swells at the mere thought of control and the unorthodox, unbound woman had an ever-so-slight dip in rights in comparison to the most obedient lass. You cannot lose much of what you barely had to begin with.

Witchcraft was a pass for humiliation and ultimately, death. The ideas associated with it, behavior wise, still persist and so the punishment continues. Marginalized women who don’t concern themselves with societies’ soulessness and aren’t emotionally caged are given to harassment in the press and via social media. As the public practice of non-Christian religions increases, particularly among Black women and women of color, “witch” isn’t an life-ending insult, even to those who don’t practice. Still, it is hurled as if it were.

In 2019, Candace Owens took to Twitter to attack Megan Markle, wife of Prince Harry, Duke of Windsor, calling Markle a “witch” and saying the prince was “under her spell.” This came after Markle opened up about the struggles she endured as a target of the press and as a new mother. During a 2021 sit down with Oprah Winfrey, Markle said the constant scrutiny and “character assassination” nearly led her to end her life. The demonization of womanhood has severe consequences.

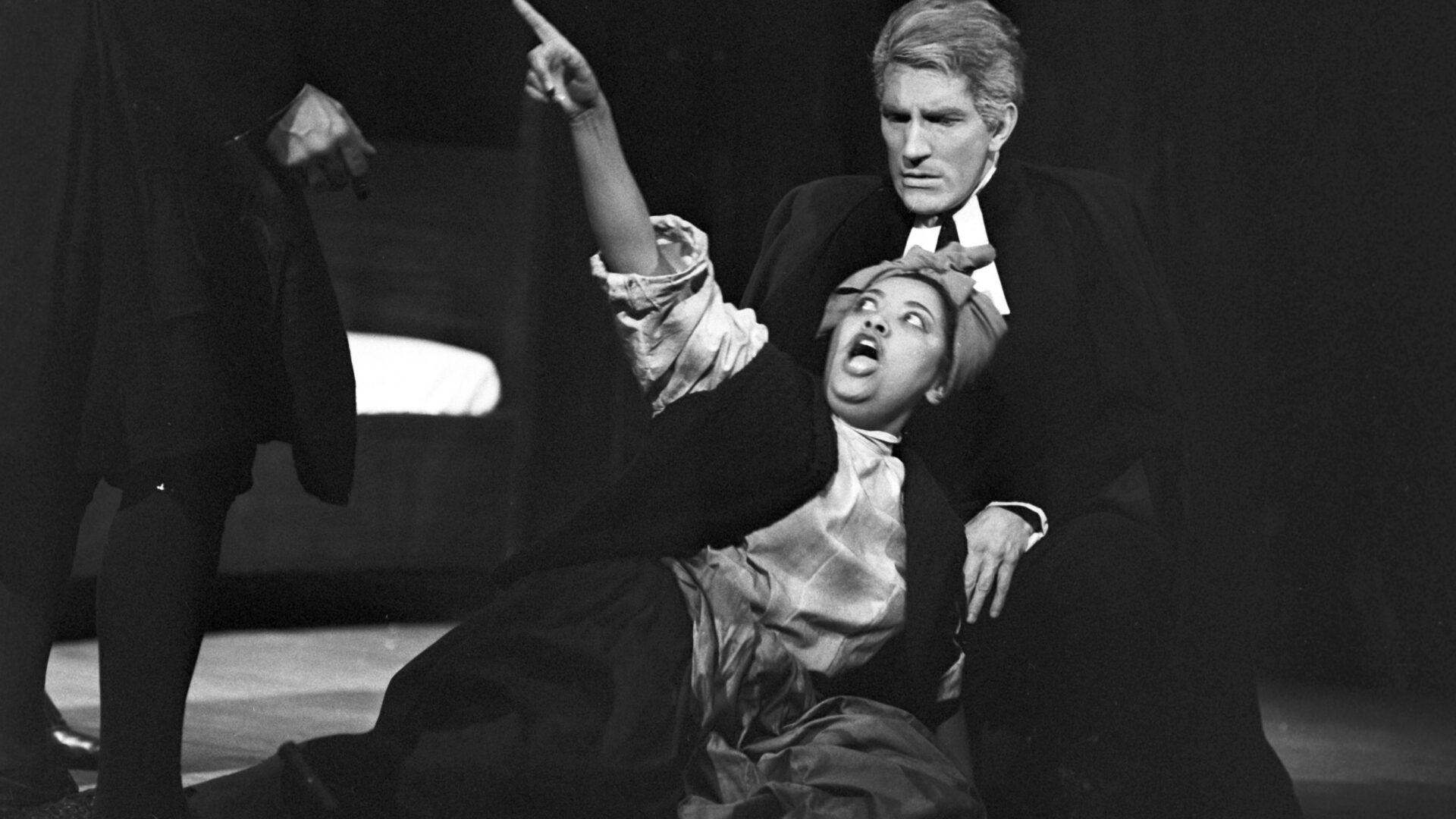

Maura Moreira (sitting) as Tituba and Helmut Ibler (kneeling) as reverend Hale during a rehearsal of a scene of opera “The Crucible.” (Photo by Roland Witschel/picture alliance via Getty Images)

When Tituba was thought to be involved with the roars and convulsions of the girls in Salem, she was allegedly beat by Parris and brought to testify before a magistrate. Set to reveal her knowledge last, she began with a denial. No doubt frightened by the high number of white onlookers, she “confessed” to speaking with the devil himself, saying, “The devil came to me and bid me serve him.” She then admitted that two other of the women accused of bringing evil to Salem, Sarah Good, a beggar, and Sarah Osbourne, a widow believed to have had an affair with an indentured servant, of becoming winged creatures before her eyes. Self preservation was all that she could focus on and if her imagination could be a shield, then she would play it up as much as she needed to.

She also told officials she had seen “two rats, a red rat and a black rat” who told her to “serve them,” witnessed more fantastic creatures, and soared through the night on sticks. She then later confessed to pinching the children. This was just the fuel the townspeople needed to confirm there was dark magic afoot. A non-white, enslaved woman was the perfect Aunt Sally for unreal “sins.”

Tituba’s personhood was enough to lead her to the gallows, yet since she had expressed true sorrow for “harming” Betty and the others, the religious folk fawned over her confession and forgave her. Forgiven but still a woman of color accused of unholy alliances (and one who recanted after admitting abuse,) Parris refused to pay her bail, leaving her to sit in jail for 15 months. She was then sold to an unknown individual for the price of her bail. She was not heard of again, at least not on public record, likely because she was an outcast.

There is no doubt that the times of Tituba have gained elasticity through oral storytelling beyond her own. Even depictions of her paint her as an older woman, though she was no more than 31 at the time of her confession. The mystery that shrouds her has only caused interest in her to grow. Her legacy has also been kept alive through pop culture references like th 1953 play “The Crucible” and Maryse Condé’s award-winning 1986 novel, “Moi, Tituba, sorcière… Noire de Salem” (“I, Tituba, Black Witch of Salem.”) Tituba’s life, as fantasy-filled as it was, is rooted in the reality of marginalized women who are guilted from creation. They unforgettably carry the blame for both the unexplainable and the most human affairs. With lower backs burning from the load and no true relief in sight, we rely on ourselves to frame our own truth. May our mouthpieces and minds be our saviors.