Megan Thee Stallion is synonymous with so many facsimiles of Black American culture. She does not borrow anything. Instead, she is a circuit channeling that current gushing identity and pride we know as Black artistry. It’s something potent, a word that most can only describe as a puissance — great power and prowess. When Megan first showed up on the scene, she had initially followed the tradition of female rappers in mainstream media. However, the truth is that Megan Thee Stallion’s inspiration stretches further than the matriarchy of hip-hop but towards the heart of the grindhouse edge of Black entertainment: the Blaxploitation era and its beloved raunchy styling.

What defines Blaxploitation, Megan’s art, and style is nothing that isn’t true to Blackness. Suppose people can confront the honesty of our identity across the numerous subnations within this constitution-bound lineage. Black American art is sexy. It is passion persevering and therefore has no other choice.

Blaxploitation started with the same clenching jaws of any mainstream effort: to appeal to the neglected demographic. Prior was an era of media that saw Black actors typecasted to particular roles that, by today’s context, are token stocks: the Mammy and the Magical Negro and the Black Tom. These roles ranged from comedic to serious to revolutionary in gender or race. They created a cultural push against particular types of representation that went against integrating Black Americans in a positive, empowered lens. Still, some intellectuals didn’t think the art was doing anything intentionally radical.

What these roles created in Black audiences was a desire for fantasy that Blaxploitation salved. It advertised itself with vibrant action and sexuality from color to styling. One of the earliest Blaxploitation films was Cotton Comes to Harlem. Its theatrical release poster, designed by Robert McGinnis, was almost entirely a panorama of lewdly glad and posed women. Rich carnelian-brown skin holds hues of red pigment and is so strikingly black that it’s almost navy. The men are pushed to the background rather than holding evidence of character are reflections of the props they use as substitutes for their being: a long magnum pistol in striking green, a gleaming gold Cadillac, another magnum prostrated in a phallic manner towards the sky and a preacher’s hand in orange.

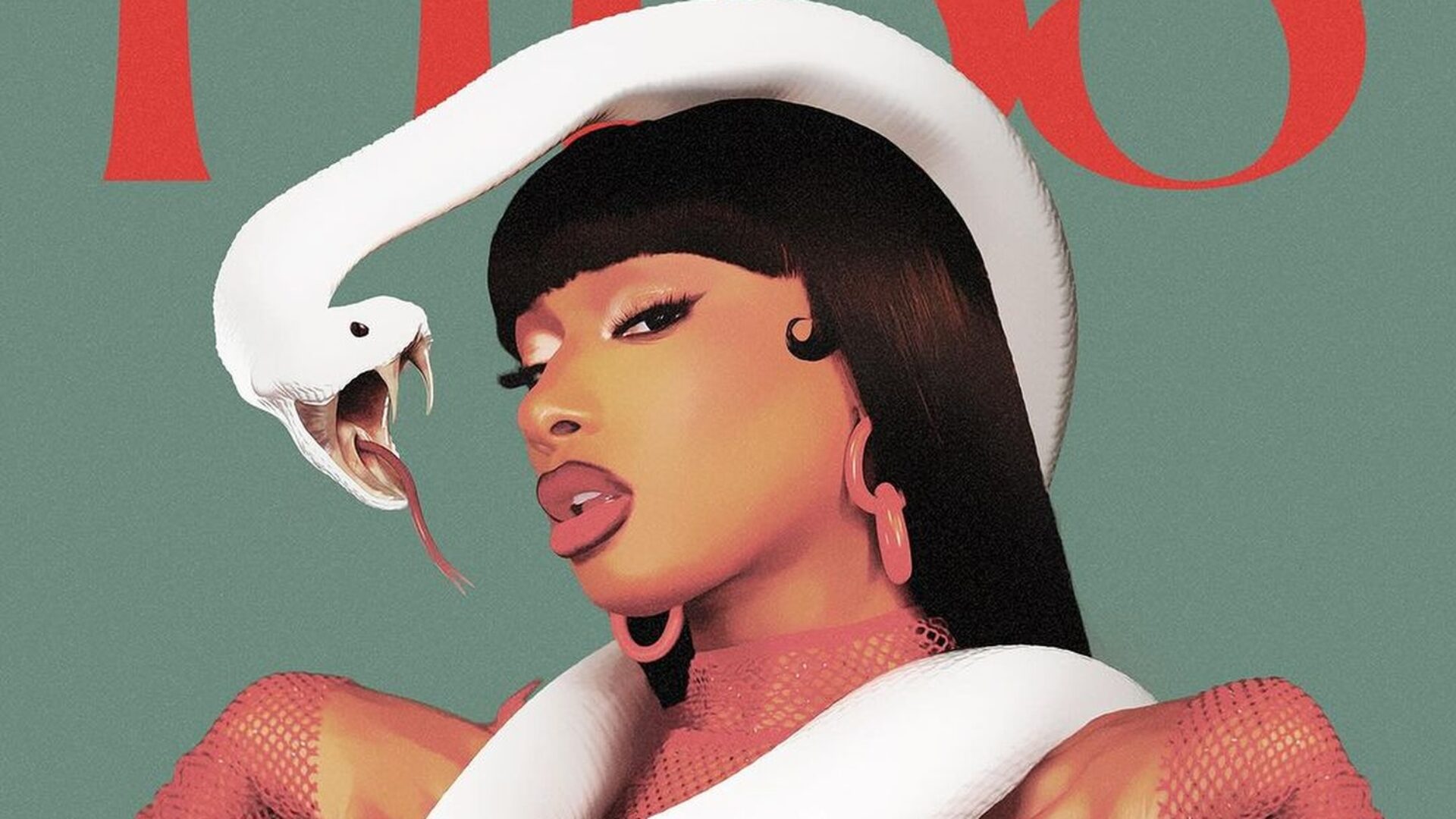

Likewise, Megan thee Stallion’s style summons similar symbols from the pin-up aesthetic. Her first debut commercial mixtape, Fever, is a direct homage to the Blaxploitation aesthetic. Megan openly references Pam Grier as a comparison for the cover art, and Pam Grier, according to a BET interview in 2023, sees a lot of how misogyny fights Meg’s presence in the industry because of the lack of ownership over her — or that she is willing to give. Pam Grier was among the first Black women to star in a Blaxploitation film. What is carried on till today by Grier is the truth: she wears her sex appeal like it’s an art. Her truth is not only a necessity but a pride, just like the stylistic choices Megan dresses with a passion disguised as rage.

“Megan embodies power to me by never publicly questioning herself or her behavior,” says Valentine Amari, a multi-disciplinary artist and performer. “She is strong-minded yet not delusional and understands that not everyone’s critique is worth respecting nor adjusting to. Her work never seems like it strives to “prove” much because who does she need to report to?” Megan Thee Stallion teases scandal in that way, reminiscent of the same Blaxploitation femme fatales who use sexuality as a disarming strike. The unquestioning nature of Megan’s style is what pulls people in. It’s what pulled people toward Pam Grier. It wasn’t about the quality of what they wore but the bravado of wearing something with unstaggering pride and the wealth of reputation over capital.

In the same provocative explosion, Megan thee Stallion’s exalted sexuality was her physical style at the time. It was successful because Megan was coming from a particular background. As Pam Grier told The Guardian in 2022, “You’ve got nudity, wet T-shirts, the dialogue isn’t that great, you can’t take them too seriously. But audiences also saw women of color stand up and speak up. Everyone knew that they’d been oppressed for so long, never allowed to fight back.”

Despite the Blaxploitation era being over, Megan’s silhouette clings to everything Grier and Blaxploitation represent as if the shadow they cast is the stage the presence of Black female style in hip hop performs on.