Every time a Black woman enters a Pilates studio, she’s stepping into a piece of Black history. Long before Lori Harvey, Black women like Kathleen Stanford Grant, a first-generation Black Pilates instructor, played a pivotal role in the history and the foundation of the workout social media has fallen in love with.

Today, Pilates, a low-impact, full-body exercise, is considered the ultimate “IT Girl” workout. However, despite more and more Black women adding the practice to their workout routine, a lack of diversity persists among Pilates studios. Like in many spaces, Black women across social media platforms have discussed the complex reality of being the only Black woman in these spaces. “I wish someone would’ve prepared me and warned me about the race disparity in pilates classes,” a creator shared on TikTok. “Being the only POC, let alone Black woman in a class, can feel lonely and alienating and take me out of enjoying the moment.”

So, in addition to building resistance to the challenging poses of pilates, most Black women are forced to build resistance to the imposter syndrome that can come with being the token in the room. While many Black Pilates-goers have learned the beauty of “taking up space” in these scenarios, organizations like Black Girl Pilates are working so that they don’t have to because of the history the Black community holds within this space. “I always let our community know that, yes, we do have a history in Pilates,” says founder Sonja Herbert.

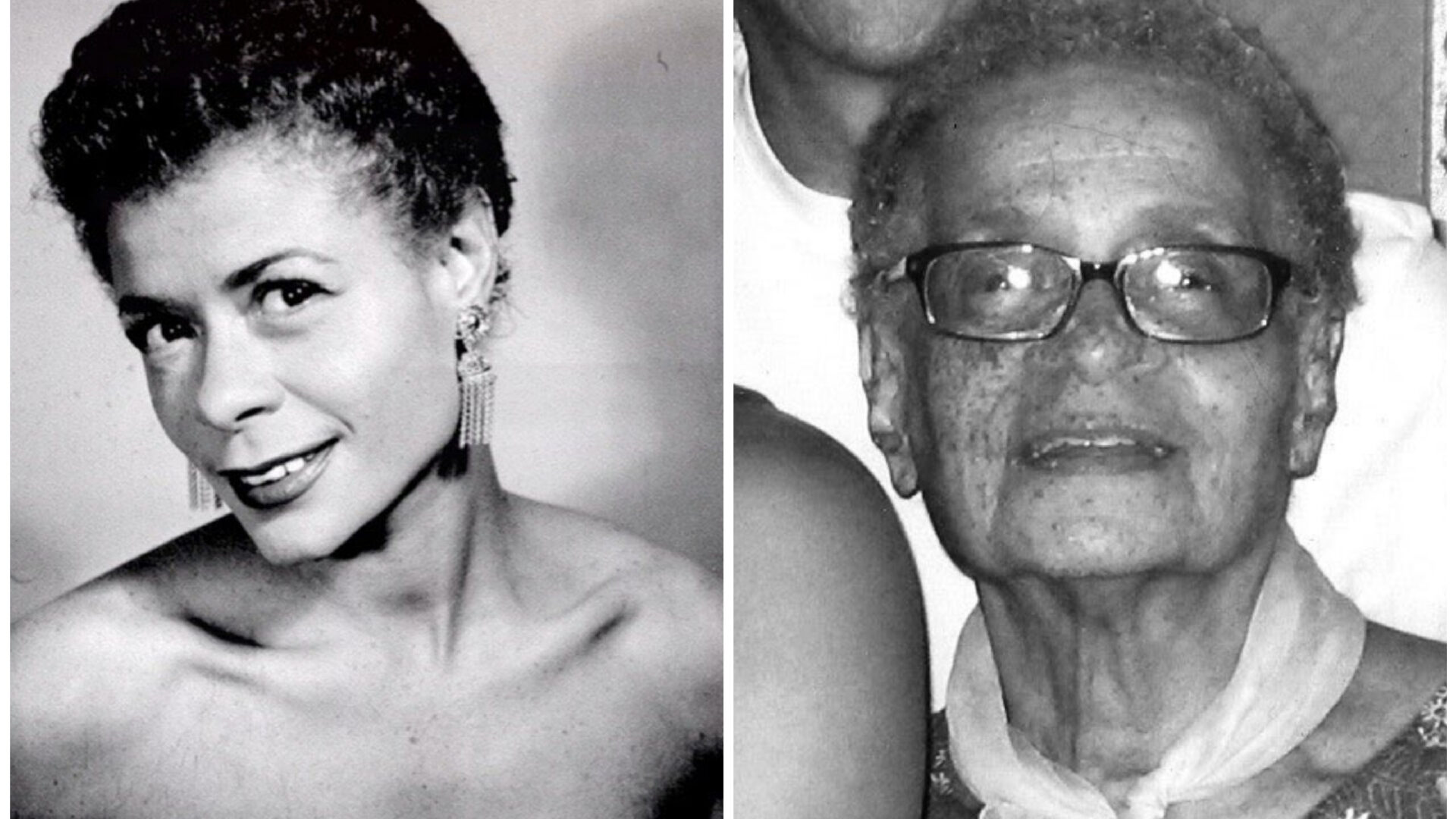

That history begins with Kathleen Stanford Grant, also known as Kathy Grant. Born in 1921, Grant aspired to become a classical ballet dancer. Becoming the first Black student to study classical ballet at the Boston Conservatory of Music, Grant’s passion for the performing arts led her to New York City. Despite the discriminatory limits the industry tried to place on Grant as a young Black dancer, she went on to star in Broadway’s first integrated show, Finian’s Rainbow, and eventually took her talents as a dancer and choreographer abroad. Her dance career quickly stopped when the trailblazer sustained a knee injury that altered her career path.

In light of the injury, per a friend’s recommendation, Grant turned to Joseph Pilates, the creator of the exercise method, for physical therapy. After seeing the benefits of Pilates’ unique technique, Grant became one of the few to learn Contrology (Pilates) directly from the inventor. After receiving her certification, she used her skills to train fellow dancers in various studios before becoming an administrator and teacher at the Dance Theater of Harlem, where she used Pilates to train young dancers.

“Now, every dancer knows Pilates, but back then, they really couldn’t afford it. Plus, they didn’t even know about it,” says Alvin Ailey ambassador and movement specialist Sarita Allen. “She had one of the first studios as a whole, not just as a black woman. At that time, only maybe three other studios in the world taught Pilates. She was revolutionary.” Allen, who worked with Grant for nearly 40 years, met her as a young dancer at the Dance Theater of Harlem.

She remembers their first encounter was not necessarily love at first sight. “We all came to Dance Theater of Harlem to do ballet, [but] we found ourselves on the floor pumping our arms and doing these crazy things, and she used a lot of vocals to activate the muscles; she used nursery rhymes,” she says laughing at the memory. “One in particular was ‘Mary had a little lamb.’ So, of course, when you’re 14, you think you’re grown […], and I just remember that I wasn’t impressed at all. I don’t, you know, that came later. Yeah, no, I think that’s common with Pilates.”

Singing was one of the many “special touches” Grant added to the practice. Known as “Kathy-isms,” Allen and other former students like Blossom Crawford of Bridge Pilates remember the Pilates pioneer using expressions that are still used today, like “zip tight jeans on, belly button to the waistline, put a belt on” to help students target specific muscles. Creating her own unique approach to Pilates, Grant prioritized both strength and healing. Beyond her teaching in Harlem and New York University, Grant helped clients, including Allen, recover from serious injuries.

“It was miraculous. A lot of the people were told, like myself, ‘You will never be able to dance again,’ Allen explains, noting that Grant’s healing work spread beyond dancers. “She trained herself. I remember her office and her home. She had stacks and stacks of magazines and anatomy books [that] she would study. That’s how she healed people. She used Pilates as the base and then her intuition.”

Gaining recognition for her training abilities, Grant worked with stars like Cicely Tyson, Eartha Kitt, and Alvin Ailey dancers. She fueled her passion for the performing arts by becoming the Clark Center for Performing Arts director and the first African-American to join the National Endowment for the Arts, where she advocated for minority dancers.

While Grant described herself as stubborn rather than genius, Allen thinks of her as a selfless badass who left a lasting impact despite her disregard for fame and inspired a generation of Black dancers and Pilates instructors. “As much as Kathy Grant was the person who ran real hard so we could walk, we also have to realize that history is being made even now,” Herbert says. “She was the beginning of it, and she opened the door so we could continue making history.”