Rapper Noname is establishing herself not just an artist, but as an activist as well. After deciding to change her name in 2016, she’s become increasingly interested in anti-capitalist initiatives after engaging in a Twitter discussion about capitalism. Then, in July 2019, she launched Noname’s Book Club, which has proven to be a safe space for radical readers.

“I feel like there’s always been a stigma on Black people and reading just because historically, we were boxed out of that process,” she told ESSENCE in 2019. “I’m trying to break apart the stereotype that n*ggas don’t read because we definitely do.” Her work is a reminder of the history of Black American literacy.

Slavery – 1700s

The history of Black people in the United States is inexplicably tied to slavery. It’s a sad truth that has continued to be an open wound for 400 years. There is evidence of ancient African storytelling, dating back to rock art that began being used to tell stories 8,000 years ago; but when enslaved Africans were brought to America, they were prohibited by law from learning to read or write. Enslavers knew that information would lead to insurrection, and attempted to bury any Black interest in the written word. One of the first anti-literacy laws, the South Carolina Negro Act (a direct response to the Stono Rebellion in 1739, a revolt that left 23 white people dead), did not explicitly state that reading was disallowed, but did ban teaching enslaved people to write. These kinds of unfair commands were in effect for over 100 years, and were used to keep Black people unaware and immobile. The following excerpt from a 1830 – 1831 law passed in North Carolina outlines the punishment for a person who ignored this particular state-wide ordinance.

“Be it enacted by the General Assembly of the State of North Carolina…that any free person, who shall hereafter teach, or attempt to teach, any slave within the State to read or write…or shall give or sell to such slave or slaves any books or pamphlets, shall be liable to indictment in any court of record in this State…“

The punishment for conviction varied by race — white men and women were fined $100 – $200 if found guilty. Free Black people were either fined, jailed, or whipped. But these laws weren’t as effective as fearful slave owners hoped. Women like Sojourner Truth and Phillis Wheatley were encouraged to pursue education. Frederick Douglass was taught the alphabet by his master’s wife in 1827, and the first HBCU was erected in Philadelphia a decade later. Truth, Wheatley, and Douglass went on to write bodies of work (in the form of speeches, poetry and articles,) that encouraged the abolition of slavery.

Post-Civil War – Late 1800s

In the decades after the Civil War, journalists like Ida B. Wells-Barnett made the Black community at large aware of racial injustices. After a friend of Wells-Barnett’s, along with two other innocent men, were lynched for defending themselves, she wrote multiple newspaper articles about their deaths. Wells-Barnett was the co-owner of The Free Speech and Headlight newspaper, the platform she used to heighten awareness about their murders, after she bought stake in the company in the late 1800s. Whites were enraged by the outlet, particularly Wells-Barnett’s work, and destroyed her writing equipment. This did not discourage her from writing, nor did it stop Black people from reading her work.

The Harlem Renaissance And It’s Effects – 1920s – 1950s

The Harlem Renaissance, a period of Black innovation across music, literature, art, and thought, in the early 1900s, gave us the works of famed Black writers Zora Neale Hurston, W. E. B. DuBois, and Langston Hughes, among many others. An interest in the progression of Black creativity helped Harlem become a mecca for talent, but white support sullied the movement. Our expression was treated as a spectacle, and some Black writers grew to hate the fact that they didn’t have the funds necessary to execute — or fully fund — their own endeavors. “It turned Harlem into a sensation,” says Columbia University’s The Rise of Consumer Culture. “A phenomenon, an event—something that Americans elsewhere in the country read about in mass-produced newspapers and magazines.”

Though the era is considered to be the peak of free Black expression, the underlying influence of commodification turned writers off. Nevertheless, the bodies of work created during the span of the first 40 years of the 20th century helped pave the way for future Black writers James Baldwin, Maya Angelou, and their peers.

W. E. B. DuBois

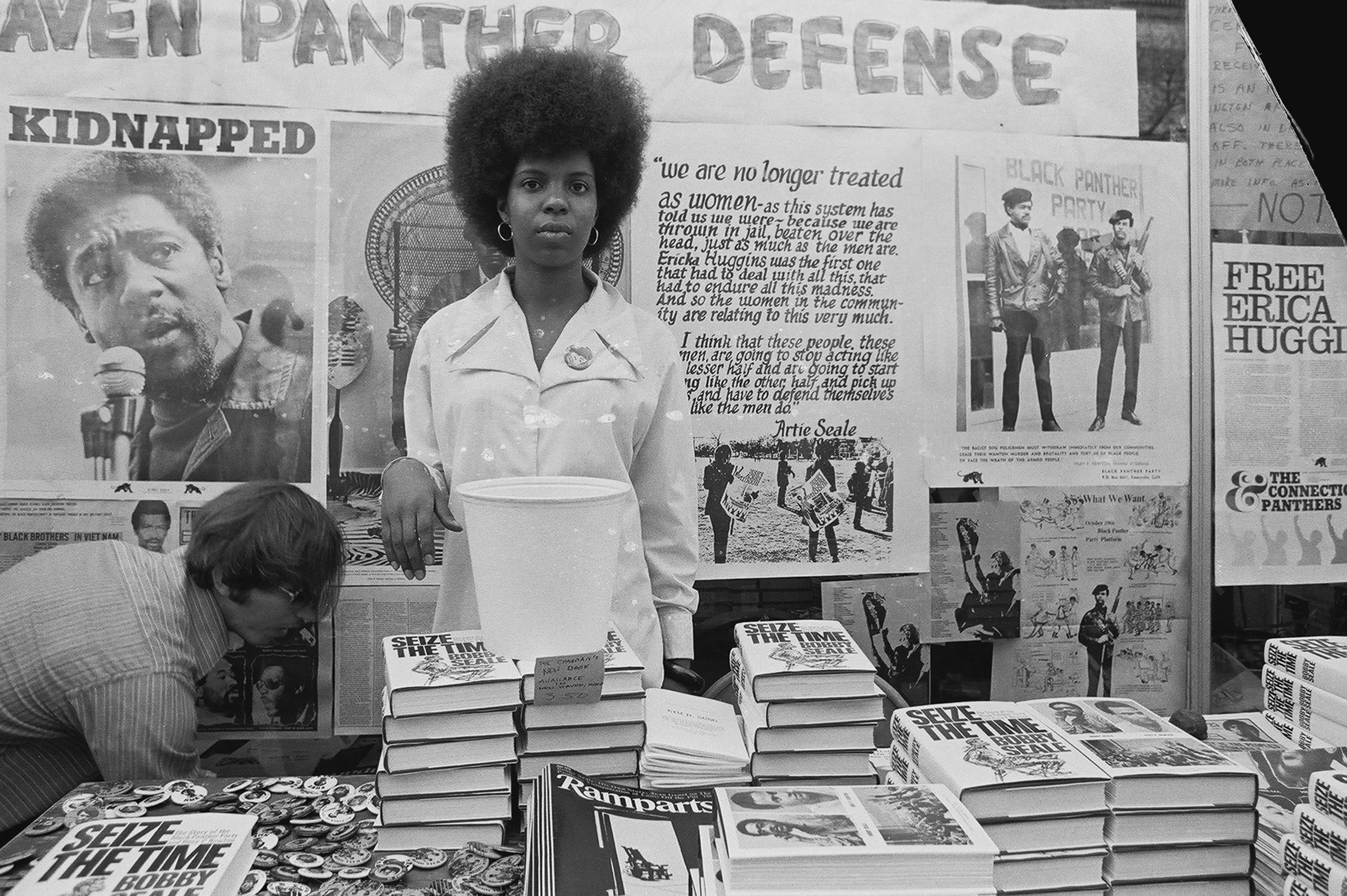

The Black Panther Party/COINTELPRO – 1960s/70s

Bobby Seale and Huey P. Newton founded the Black Panther Party in October 1966. This organization originally aimed to protect Black community members from police brutality; yet, it quickly evolved into a political party that included a free breakfast program, a push for reparations, among other major resources. As the Black Panthers mobilized, the FBI’s COINTELPRO (the Counter Intelligence Program) took note and began to stifle the party’s progress. Even non-radical spaces, like Black owned bookstores, were targeted.

In 1968, J. Edgar Hoover, the Director of the FBI, notified COINTELPRO agents that bookstores were hubs for the distribution of politically extreme materials. Hoover instructed offices to keep an eye on any Black owned bookstores, regardless of if they were tied to leftist activists groups or not. Washington, D.C.’s Drum and Spear Bookstore (which was founded by former SNCC secretary Charlie Cobb) was relentlessly attacked because of the stores proximity to the FBI headquarters. “It wasn’t uncommon to see Toni Morrison and Amiri Baraka browsing the shelves alongside diplomats and regular folk,” said Mills College professor Daphne Muse. Though the store closed in 1974 due to the insustainability, it remains a reminder of the threat surveillance and government interference present to Black movements.

As the Black Panther Party’s power waned, Toni Morrison, Ntozake Shange, and Alice Walker began telling the stories of young Black women who were finding themselves in a racist, sexist world.

The Dominance of Black Women’s Lit – 1980s/1990s

Alice Walker’s 1982 novel, The Color Purple, was a look into the life of Celie, a young Black girl in pursuit of freedom. The men closest to her abused throughout her life, rendering her nearly incapable of self love. The true heroes of the book are the women who help guide Celie back to herself. It was turned into a Steven Spielberg-directed film in 1985, and was nominated for 11 Oscars, including Best Picture.

One of the biggest criticisms of the work of Black women authors during this time was that their work was hyper-critical of Black men. The New York Times’ 1986 piece called “Sexism, Racism and Black Women Writers” reads, “But, for some, Miss Walker’s skill as a writer was partially obscured by her one-dimensional portraits of black men. And, even at that time, there were murmurings and complaints about the alarming increase in stereotypical fictional portraits of black men as thieves, sadists, rapists and ne’er-do-wells.” The article also likens Walker’s most famous work to Shange’s “For Colored Girls Who Have Considered Suicide/When the Rainbow Is Enuf” and Morrison’s “The Bluest Eye.” When writer Charles Johnson was called on to comment on Morrison’s 1993 Nobel Prize win, he spoke on his belief that her highly politicized work was bound to be offensive.

“But when that particular brand of politics is filtered through her mytho-poetic writing, the result is often offensive, harsh,” Johnson told The Washington Post. “Whites are portrayed badly. Men are. Black men are.” So, even though Black women were receiving major accolades for their work, their honest stories of Black men were enough to alienate certain readers. But, was the work really for them, anyway?

A Legacy – 2000s/Present

Noname now proudly refers to herself as a librarian. Her bookclub is an investment in the lives of Black people and people of color across the country, and combats corporations who want to capitalize on literary interest. Noname’s Book Club joins the likes of Well-Read Black Girl and Black Girls’ Book Club, organizations that understand America’s fraught relationship with Black literature.

Books are nowhere near obsolete, but many of the writers of today share their work online. The advent of social media makes accessing writers and their words that much easier. This has proved to be a blessing and a curse — readers can access a published piece with ease, but also can attack the writers for their ideas, which has proven to be a serious issue for Black women who are visible.

But in the midst of the madness, we’re still reading and writing. Just like we’ve been doing.

Photo Credit: Twitter