I was three years old when Hurricane Katrina struck New Orleans. I vaguely remember waddling to my dad’s loaded SUV; my little fingers interlaced with my mom’s as we hastened through the doorway, half-prepared to brave the unknown. I may not recall much, but I recognize the warmth of my mom’s hand. It served as a poignant aid of comfort to my nascent curiosity. I was a wide-eyed sponge of knowledge, awaiting our next adventure while ominous clouds loomed above our heads. Yet, I wasn’t paying attention to the impending danger around me. To me, this was a mini family getaway, and I’d return home in a few days to be greeted by the stuffed animals perched atop my bed. My mom told me I left my first baby doll and a stuffed teddy bear behind on the bedroom floor when I got older. “I feel something big is coming,” my pawpaw warned my mom about a week before the storm reached landfall. “We have to go,” he alerted the whole family. A sharp, intuitive soul, my grandfather was a crucial figure in our decision to relocate to Houston during the tropical cyclone. I’m not sure where we would be without his life-altering input. All I know is that after leaving, I never saw those plushies again.

Twenty years ago, Hurricane Katrina left a painful imprint on the community of New Orleans. By August 31, 2005, 80% of the city was underwater. However, some of the areas most impacted included the Lower Ninth Ward and New Orleans East. Vacant homes, empty lots, and boarded buildings still plague the predominantly Black neighborhoods due to resource scarcity. As payday lender services, fast food chains, and dollar stores seemingly fill every block, the ghost of what used to be continually haunts its remaining inhabitants. Before Hurricane Katrina, New Orleans East had an estimated population of 125,000 residents. As of August 2025, that number stands at around 88,000. According to WDSU, the Lower Ninth Ward had a population of about 14,000. In 2023, the citizenry was around 5,000, a 65 percent decrease in the number of people. Many residents reminisce about the old businesses, homeowner dominance, and accessible recreational activities that were available to the community before the disaster. Beyond its literal implications, the expression “before the storm” echoes a collective wistfulness so strong that the phrase is standard New Orleanian household vocabulary. Young adults often recount the sentimental memories that their parents shared with them, including my own.

Notably derived from the 2022 HBO documentary of the same name, the term ‘Katrina babies’ describes the young children impacted by Hurricane Katrina. Presently, these ‘Katrina babies’ have reached adulthood, some faintly retaining the repressed memories of their caretakers. Others experienced the aqueous catastrophe in greater detail. These are their stories.

Darrin Francois, 25

“We had left our house in the East at the time,” Francois began. Francois lived with his mom and three siblings. Due to the threat of rising floodwater, his aunt advised them to relocate to the top floor of her apartment complex in the Iberville Projects. Francois, his mom, three siblings, his aunt and her boyfriend, and two cousins were under one roof on August 29. They experienced a severe power outage in the area, surrounded by extreme flooding. “Once everything calmed down, we started heading towards the Superdome,” he stated. While Francois’s mom, aunt, and his aunt’s partner waded through murky waters, the young children were pushed in mail carrier totes toward the domed stadium.

“When I got to the Superdome, all I could remember were the people all around me who looked so worried. We just saw a lot of suffering.” When transit buses arrived at the Superdome on September 4, Francois boarded with his mom and aunt, while the rest of his family got on the bus behind them. “We hadn’t eaten for days, so my mom gave me some food that they had on the bus,” Francois commented. “I thought I was going to die without eating,” the 25-year-old recalled. The next day, Francois and his family arrived near Beaumont, Texas. They stayed in a shelter for a week before moving into an apartment building in Baytown, where the complex distributed housing vouchers to Katrina survivors. Francois lived there for two years following the hurricane’s wake.

Jonnae and Shaundrea Sylvester; 23, 22

A sea of water. That’s the clearest memory that Jonnae Sylvester, 23, recollects. Like Francois, Jonnae, and her younger sister, Shaundrea, were among the families rescued at the Superdome. “When rescue finally came, they just put you on a helicopter and took you wherever. You didn’t really know where you were going,” Jonnae told GU. Although the aircraft landed in Houston, the Sylvesters moved to San Antonio, fearing the likelihood of mass displacement. “I was so curious about what was happening and why there was so much water around me.” Raised by a teenage mother, it was critical for the Sylvester sisters not to forsake their hometown, given their hazy memories of the Big Easy. And their mom, Shaundreca, made sure of that. “When the Saints won the Super Bowl while we were in San Antonio, I remember my mom telling me, ‘Your home will always be New Orleans.’”

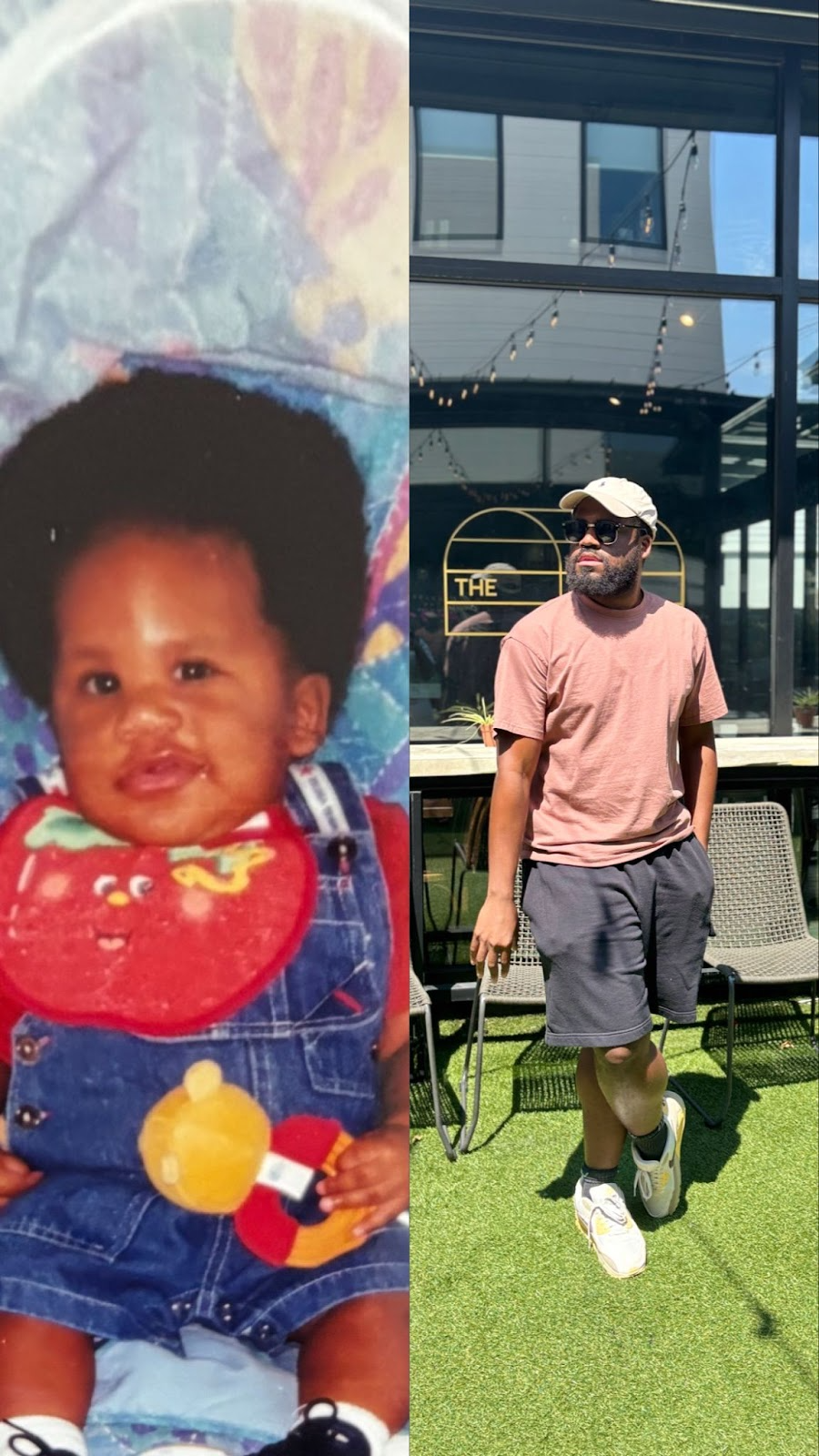

Despite the siblings losing the bulk of their baby photos in the storm, their mom urged them to photograph every special moment going forward. “My mother made sure that while we were in San Antonio, she took a bunch of photos.” Shaundrea Sylvester, 22, only remembers what her mom tells her about the storm, being only two years old at the time. “I can’t remember much at all but the chaos,” Shaundrea expressed. A clip of the sisters’ mom walking out of a store, food in hand, was aired in the 2025 National Geographic documentary series, Hurricane Katrina: Race Against Time, alongside other films about the hurricane. “My mom walked through the water to get food for me and my sister, knowing she couldn’t swim,” she said.

Jonathan Hicks, 26

“When Hurricane Katrina came, I actually left,” remarked Hicks. At the time, Hicks was staying with his grandparents while his parents were on a trip in New York City. Despite being out of state, his parents tracked the storm’s trajectory and decided to evacuate the city after reuniting with Hicks. His family packed their items in a U-Haul truck and headed straight to San Antonio. “Luckily, we left before the storm came,” Hicks admitted. “My mom was the one who said we should leave immediately.” The tropical cyclone’s unpredictable outcome instilled a sense of dread in a young Hicks, mostly due to his lack of situational awareness. “I didn’t understand what was going on,” he said.

Hicks resided in San Antonio for three months before moving back to New Orleans. “To say we came back home to see a majority of our things damaged…it was hard,” the 26-year-old recounted. Shards of glass, splintered trees, and hanging wires filled his neighborhood block, creating a danger zone. However, as an adult, Hicks still credits much of his youthful naivete for misunderstanding the cumulative impact of Katrina. He discovered most of Katrina’s true detriment through documentaries, real-world encounters, and the stories of his mother. “It’s crazy that a lot of hospitals, homes, and communities are still unrepaired twenty years later. It’s way past due,” he shared.