This past summer, we all clamored to get tickets, eagerly awaited our tour dates, and wore meticulously planned silver outfits to witness the brilliance of Beyonce’s Renaissance World Tour. The tour and the album of the same name inspired thousands of us in the Beyhive to “release our wiggle” and experience a new birth and a new day. We watched Queen Bey take the stage and reinvent her image, pay homage to past archetypes, and give us a safe space to just be. That feeling of safety, creative freedom, and revival serves as a microcosmic world akin to the decade now known as the Harlem Renaissance.

The Harlem Renaissance is mainly due to the Great Migration, a period in the 1920s in which roughly 800,000 Black people moved upward from the South, Midwest, and Caribbean to escape harsh discrimination and pursue an autonomy never known to them before. With this newfound autonomy came the desire for creative expression, and with a 200,000 influx from the Black Migration, Harlem quickly became the hotspot for Black creatives, many of whom are now notable influences in music, fine art, literature, dance, and fashion.

Fashion in Harlem

Born from the new age was the new woman. We are now post World War I and the post-19th amendment that granted white women the right to vote. Black women, unsurprisingly, were not granted this right until 1965; however, the passing of the 19th amendment did directly coincide with women’s general interest in fashion as creative expression – like always, Black women led the way. Influencing major players like Vogue, Holly Alford, author of the seventh edition of “Who’s Who in Fashion” and assistant dean and VCUarts director of inclusion and equity, has said,” All the top designers were going to Harlem to knock off the stuff they found at the fashion shows held in the streets.” History really is cyclical.

Source: Black Quotidian.

Originating in France, fashion shows didn’t make their way to the U.S. until the early 20th century, but once they arrived, they quickly became one of America’s favorite pastimes. A quick search for “Fashion Shows” between 1920-1939 in the Library of Congress’ Historic American Newspapers database loads hundreds of results. Due to Black people being excluded from mainstream fashion spaces, many sewists would market and sell their designs within their communities despite their newfound capital. As fashion shows became popular in the U.S. amongst whites, Harlemites realized they could create their own shows, showcasing the talent in their neighborhood. Often held in churches, historically considered a safe space for us, many of the shows were nothing like what we’d expect today; instead of strutting the runway, models would center themselves on stage, give a playful twirl, and orally deliver the details of their fashionable garments. These fashion showcases would mainly be organized by women in the community to bring awareness to specific causes or as tools for community building – dancing, drinks, and camaraderie typically followed.

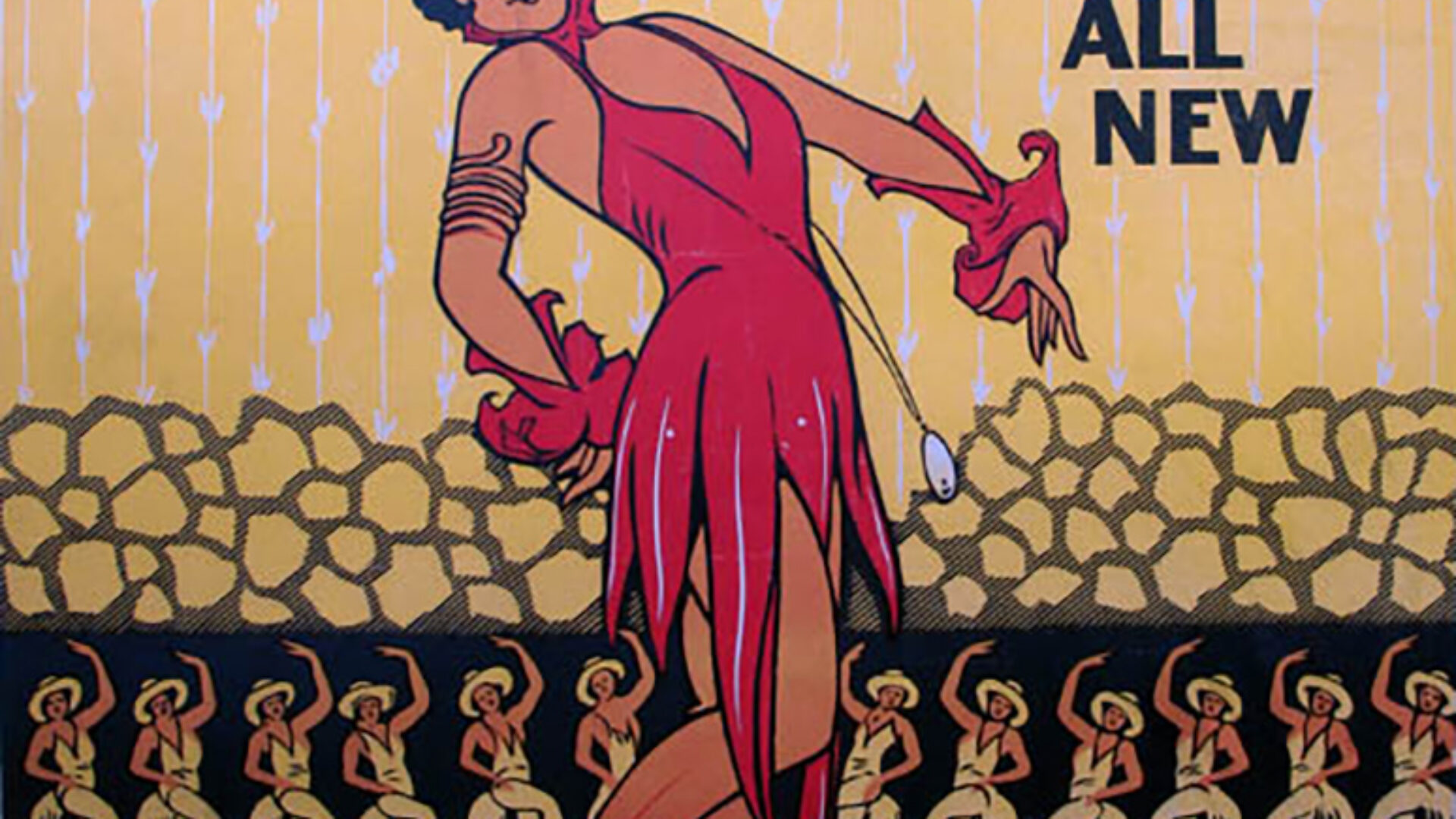

While White America had the Ziegfeld Follies revue, it took mastermind playwright and producer Irvin C. Miller to make it Black and “make it fashion” in a way that only we know how. His wildly popular act with nationwide stops, “Brown Skin Models,” emphasized the inclusion and uplifting of Black beauty standards. It is said to have revolutionized fashion shows by allowing the focus to be exclusively on the models and their garments. In Ziegfeld Follies, the models sang and danced – putting on full performances. Miller’s models strutted, posed, gave smize, and let the clothes do the talking. Entertainment, like the Harlem Swing Band, was allotted to the background and became soundtracks for the sartorial experience. This became known as “fashion walking” and is like what we see at Fashion Weeks globally today. “Brown Skin Girls” was a coveted ticket in every city it traveled to, and even stopped at Army camps during World War II.

Beyond the Renaissance

Though Harlem laid the foundation, Black Americans of every decade have adopted the idea of using fashion shows as a device for community capital and social change.

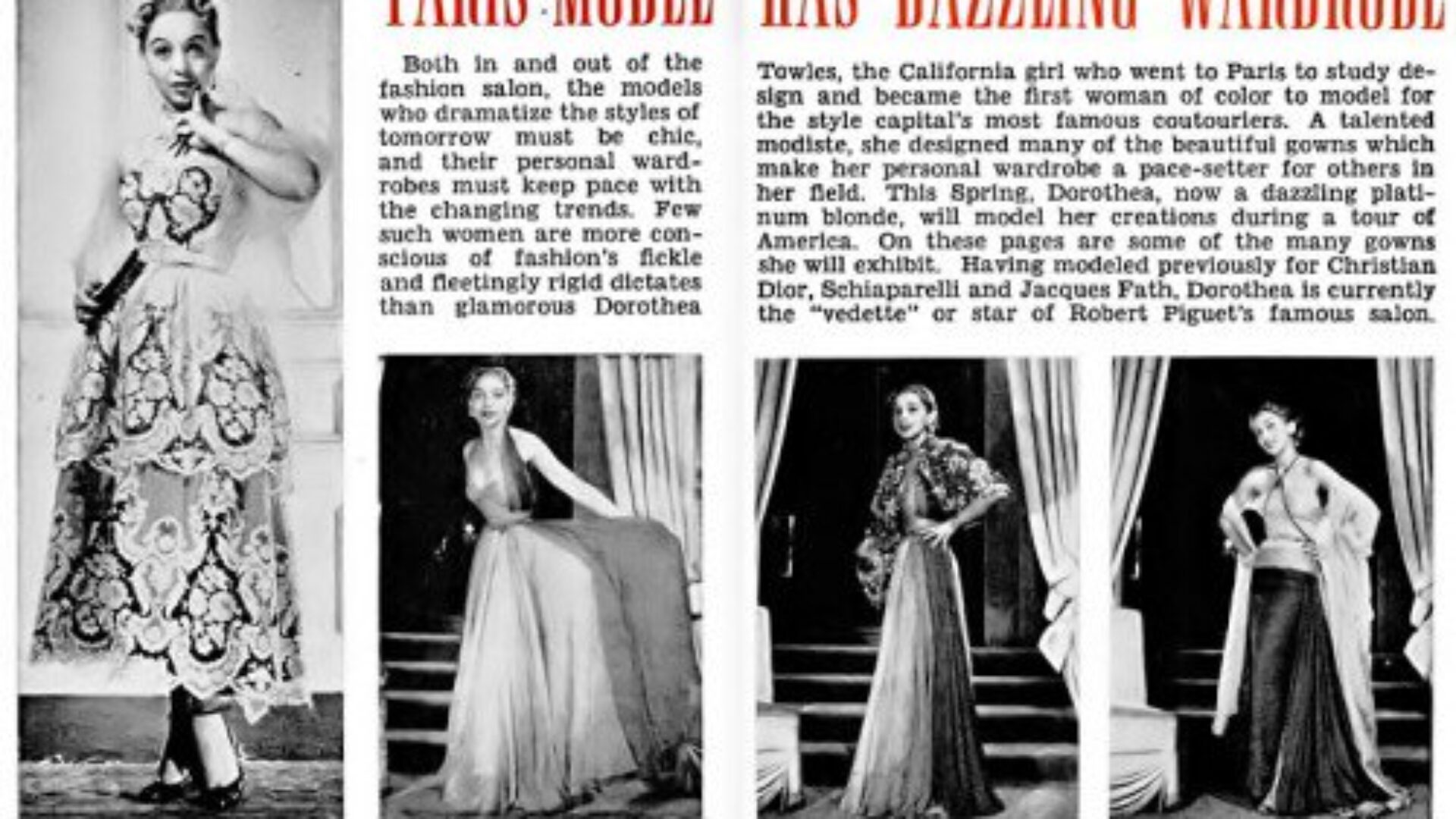

In the early 1950s, Dorothea Church, the first Black woman to model haute couture for European brands, returned to the United States, struggling to find work. Not one to waste time or a suitable gown, she found communal use of the couture she’d purchased in Paris. With the help of Alpha Kappa Alpha, she arranged fashion shows at HBCUs around the country, recruiting and teaching local professionals and aspiring models the tricks of the trade. Her willingness to share her craft contributed to the wave of Black models being hired in the early 60s and helped to raise money for the hosting universities.

Naturally, 62’ was held in Harlem, coinciding with the Civil Rights Movement. Naturally ’62: The Original African Coiffure and Fashion Extravaganza Designed to Restore Our Racial Pride and Standards put the “Black is Beautiful” movement in motion. The Grandessa models had fuller figures, were darker skinned, and had natural hair – all taboo at the time. Many of them made their threads all African-inspired. It was an active fight against colorism and textures and a call to return home, and it was successful! The Afrocentric aesthetic gained popularity, most visibly inspiring political groups like the Black Panther Party.

Source: Kwame Brathwaite Archive/Philip Martin Gallery LA

Today, companies like Harlem’s Fashion Row, founded by Brandice Daniels, provide Black designers, models, and media mavens with mentorship and life-changing partnerships that ensure they will thrive in spaces still intent on excluding them.

Regardless of our roadblocks, we continue to innovate, inspire, care for our communities, and set the bar – and look good while doing it. Word to Giselle, the Renaissance is not over.