According to the American Psychiatric Association, only two percent of the 41,000 psychiatrists in the United States are Black. Shocking, but not really.

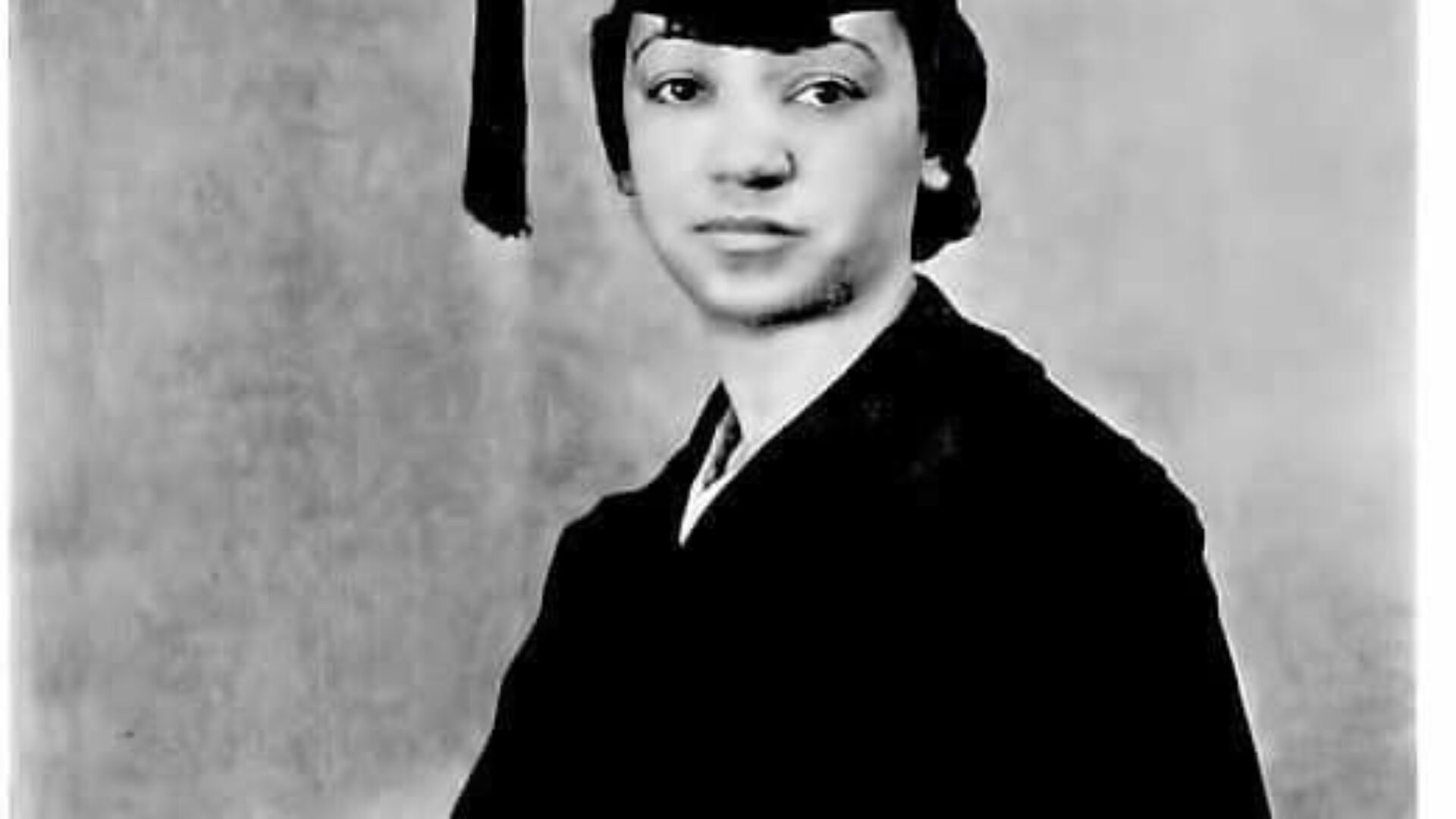

Before there was any record of Black psychiatrists, psychotherapists or psychologists – male or female – there was an unsung hero who made it all possible for Black people to feel seen in spaces of mental health in a world where mental health disparities, illnesses and issues impact us at a disproportionate rate. This unsung hero’s name is Inez Beverly Prosser, PhD.

“At this time, particularly it being Women’s History Month, I think it is so important to pay tribute to all female innovators whom have paved the way in all career fields. As a Black female clinical psychologist myself, Dr. Inez Beverly Prosser is an inspiration to me,” said Desreen Dudley, PsyD and Teladoc Senior Behavioral Health Quality Consultant. Dr. Dudley continued to pay homage to the late Dr. Prosser as someone who has paved the way for her own vision of working as a clinical psychologist. “I celebrate the accomplishments of Dr. Prosser because she has made it possible for other Black women to envision themselves as clinical psychologists who can contribute to supporting the emotional and social needs of all people, with representation and cultural sensitivity to particularly people of color, and offer diversity to the field of psychology.”

As a Black woman in Jim Crow America, Prosser encountered much adversity and pushback to pursue a doctoral degree in psychology. Born in San Marcos, Texas in 1895, Prosser was one of 11 siblings and started an “educational fund to help her siblings attend and complete high school and college,” according to GoodTherapy.com.

After graduating at the top of her class from both her high school and Prairie View State Normal and Industrial College (now known as HBCU, Prairie View A&M University) in 1912 with a teaching certificate, Prosser began to teach around the Austin area until 1927. Because the state of Texas didn’t award graduate degrees to Black folks at the time, Prosser got her master’s degree in education from the University of Colorado, where she also took psychology courses.

Though she was denied access to every psychology graduate program in Texas due to her race, she persevered and earned a doctorate in education from the University of Cincinnati in 1933 – thus making her the first Black female psychologist, reported by Psychology Today‘s Ava Floyd, MA. That same year, she was featured on the cover of NAACP’s official magazine, The Crisis.

Her practice focus included the psychological impact of racial segregation and integration in schools on the self-esteem and wellbeing of Black children. In her dissertation, The Non-Academic Development of Negro Children in Mixed and Segregated Schools, Prosser further evaluated the direct relationship between racism and racial inequalities to the mental health of Black children, as well as the difference between the mental health of Black students in segregated and integrated schools.

“As a clinical psychologist, and new mother, Inez Beverely Prosser’s work remains relevant as we make decisions about the academic environments we want our children in,” said clinical psychologist Gillian Scott-Ward, PhD. “Her work taught me that perhaps we need to evaluate academic environments with nuance; considering not only the rigor of educational offerings of a school, but the ability of Black children to thrive there emotionally, socially, and psychologically.”

Dr. Scott-Ward continued: “The foundation of the well-being of Black children is dependent upon the environment’s ability to create in them positive self-regard, healthy social connections and appropriate support that reflects and values their uniqueness.”

Prosser later became a professor at Mississippi’s Tougaloo College and a financial benefactor for Black undergraduate and graduate students. While at Tougaloo College, she also acted as registrar and dean. There, Prosser also received a grant to conduct doctoral research in teaching and education. In 1934, she died in a tragic car accident around the age of 39 – just a year following the receipt of her PhD.

Photo Credit: Horizons National